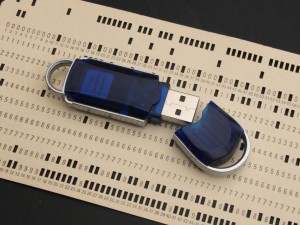

Carry your entire medical history with you, in your pocket.

Never forget your doctor's appointment or to take your medication again.

Use your smartphone, cell phone, or PDA to access your records on the go!

Securely store your medical records such as X-Rays, test results and doctor's notes.

Before electronic health record (EHR) and personal health records (PHR) technology becomes mainstream and widely used, those who are utilizing it will need to change their security habits. A nation-wide push is going on to propel our healthcare system into the 21st century and (finally) go electronic with our health records. With that push, however, comes stories of stolen laptops, missing printouts, trashed hard drives still containing data, and more, all potentially putting patients by the tens of thousands at risk of having their records fall into the wrong hands.

Before electronic health record (EHR) and personal health records (PHR) technology becomes mainstream and widely used, those who are utilizing it will need to change their security habits. A nation-wide push is going on to propel our healthcare system into the 21st century and (finally) go electronic with our health records. With that push, however, comes stories of stolen laptops, missing printouts, trashed hard drives still containing data, and more, all potentially putting patients by the tens of thousands at risk of having their records fall into the wrong hands.

Nearly every one of these compromises is not due to sophisticated hacking or electronic breaching techniques. They’re almost all because of stupid mistakes made by people who should either know better or have been taught better.

There are two types of medical records: those kept by doctors, hospitals, clinics, and the like and those kept by patients. An electronic record can be either, but generally, the term “EHR” is used to denote a record kept by hospitals, doctor’s offices, or even insurance companies. The term “PHR” always refers to patient-held or controlled records, such as MedeFile or the now-defunct Google Health.

A few examples of common breaches of EHRs and how they could have been prevented with simple, common sense security. Often, the kind of security you would think would be the norm, but is often not. Nearly all of these involve EHRs as, to my knowledge, no serious (large scale) breach of personal health records has ever occurred.

Example 1: In San Francisco, the medical files belonging to nearly 300,000 California patients were on an unsecured Internet website where anyone who wished to look could see them. These included insurance forms, Social Security numbers, doctor’s notes, and more. The information was, literally, available to anyone who wished to Google it.

The problem? The company that held the records, a company called Southern California Medical-Legal Consultants (a worker’s compensation payment firm for doctors and clinics) placed the records on the website. The person doing so assumed (never assume) that the site was only accessible to employees. There was no password required and no robots.txt file instructing search engines not to index the files.

Example 2: Another California hospital, his one in Palo Alto, caused 20,000 emergency room patient records from Stanford Hospital to be placed on the Internet for all to see ñ staying online for nearly a year. The data, contained in a detailed spreadsheet, was given to a vendor (a billing contractor called Multi-Specialty Collection Services). Someone there placed the file on a website forum asking about how to mainpulate spreadsheet data to get various types of graphs.

The problem? Again, an outside contractor is given the data and someone who was obviously not trained well in data security posted the whole spreadsheet, full of patient data, on a public website where it stayed for almost a year.

In both examples 1 and 2, one common denominator in security protocol and another common one in accountability are highlighted. The first is the fact that this kind of sensitive information should not be allowed to be placed in public places. Security at these vendors should include blockages that keep data from being put onto devices that can be removed from the secure premises, from being put on public websites/servers, and from being transferred at all without prior authorization. That should be standard practice for anyone handling sensitive, personally-identifiable information like patient records.

The second trend is in the myriad of vendors and second- and third-hand groups that receive confidential patient information from doctors and hospitals. Most are, of course, just honest people providing vital services, but the further away from the patient records get, the less stringent the security around those records seems to be.

Sometimes, though, it’s not outside vendors to blame, it’s hospitals or doctor’s themselves. Such as when 6,800 patient records were disclosed on the Internet when protocol was breached at the Columbia University Medical Center.

The real trouble, ultimately, is accountability. Unless actual financial damage occurs (and it can be directly traced to the lost records), nobody ends up in any real trouble. At worst, they usually get audited or lectured by regulators and perhaps a bad headline or two in the media. On very rare occasions, they must pay money to those whose records were lost. Rarely is the one paying the third party vendor or the person who actually put the records at risk.

Interestingly, with PHRs, the opposite would be the case. Those who keep personal health records are directly tied to the patients for whose record it is. If the record gets stolen, compromised, or otherwise put at risk, patients know exactly who to hold accountable and we lose business and valuable reputation if we make those mistakes.

This kind of accountability means that PHR makers and holders put a lot of concerted effort into making sure that breaches don’t happen. This should be the standard throughout the medical records industry.

- By Kevin Hauser Submitted on January 23rd, 2012